INTRODUCTION

Sport and Physical Education play a significant role in the total education of pupils, allowing the acquisition of competences such as: cooperation, mutual help, reflection and the management of future physical life. (Boudinar, Joly & al, 2006; Beaucher, 2012). It’s also an interesting discipline for the development of children with disabilities and it must be adapted, reassuring and progressive. (Zicola, 2000, 2008). Sports activities must be adapted to the motor skills of children with special needs. (Marcellini, 2005; Platt, 2001). Faced with their reduced mobility and their handicap, they often underestimate their true capabilities. (Brunet, 1997).This physical practice has advantages at different levels. (Boudinar, Joly & al, 2006; Gaillard, 2007, 2010). At the physical level, physical activity can develop the basic physical qualities such as: the rediscovery of the pleasure of movement, the fight against muscular atrophy and the prevention of complications related to inactivity. Psychologically, it helps pupils with difficulties to promote better self – esteem and to regain confidence in their possibilities and restructure their image. Socially, sport helps the handicapped to fight against boredom and isolation. By dint of these benefits, it is logical that students with special needs seek to take part in sport and physical activities and to be considered like the sportsmen and the others. Indeed, the Salamanca Statement (UNESCO, 1994), proclaimed that children “with special educational needs, must have access to regular schools which should accommodate them through a child centered pedagogy capable of meeting these needs “. In Tunisia, disability is the primary cause of discrimination. Because, a handicap frightens, feeds the taboos, the disabled are victims of daily discrimination (Ben Abderrahman, 2011). School integration of students with disabilities, is no exception to this rule. (Ouertani & Elloumi, 2011; Elloumi, Ouertani, Behri & al., 2012). It is then a question of rethinking the reception of the pupils and to wonder at the same time about the conditions of such a reception as well as about the organization of the physical and sports activities within ordinary and specialized institutions with the aim of changing attitudes towards disabilities. According to the official figures, 2 % of the Tunisian population have a disability. Indeed, there are 336 integrated schools welcoming 1496 disabled children (2009-2010); more than 200 preparatory classes are open to the disabled children in schools; in approximately 40 intermediate schools there are 170 registered disabled pupils. Finally 343 specialized centers welcome mainly children and young people with a disability. (Louhichi & Chbil, 2013). In front of this alarming situation and according to the legislature about integration of the handicapped in the intermediate schools in Tunisia. “The right of the handicapped person for an appropriate education was expressly recognized by the law N 81-46 of May 29th, 1981 relative to the protection and to the promotion of the handicapped persons was modified by the law N 89-52 of March 14th, 1989 which stipulates in its article six That: “the handicapped persons have the right to benefit from education, reeducation and from an appropriate vocational training”. This right is confirmed by the law N 91-65 of July 29th, 1991 relative to the educational system. This law made the education of the disabled an integral part of the general system of education and consolidated the exercise of this right by diverse measures facilitating the access to the instruction for the largest number of handicapped persons. (Law n° 2005-83 of 15 August 2005). This law insists on the right to education for all the children, regardless of their disability. Today, the achievement of equal opportunities for all (Boudon, 1973; Duru-Bellat, 2002) is the first contribution of the School in the realization of the ideals of the Republic. So is born a barrier which is translated in social inequalities (Etienne, 2008; Jenkins, Micklewright & Schnepf, 2008). The Charter of Human Rights and citizenship stipulates in article I that “the people are born free and equal, in dignity and in rights.” To allow the integration of the pupils with special needs, the teacher must know the peculiarity of the handicap and the singularity of the individual student needs, his possibilities as for the apprenticeship within the physical and sports educational discipline and more generally the integration issues within the class. (Berzin, 2007; Indermuehle & Borserini, 2010). This will of integration is not only political, the parents of the handicapped children also wish for an integration in ordinary schools (77 % of the parents wish that their child gets a normal schooling, even if it is a specific class) (Blin, 1998). Postic (2002) showed that the sick or handicapped children are already isolated because of their disease and because of their care, they do not have friends, the sport can bring them what they need more, a need more important than the others: social relationships. It seems then important that the institution adheres to the principle of training the future teachers to deal with the pupils with specific needs so that their integration is feasible and accomplished (Berzin, 2007; Dubois, 2011). It is also important as to achieve a successful integration that the teacher work and experiment within an educational team but also interact with the pupil and his family to become more informed about all the specific needs of the pupil. (Columna, Foley & Lytle, 2010; Cachot & Poncet, 2013). Feuser (2008) developed a concept of pedagogy which allows an integrative education of all the children with particular needs, independently of the type and of the degree of handicap (various disorders and different pathologies). For that purpose, the teacher is going to set up educational strategies which answer these needs. It is also necessary to know the specificity of the handicap and the peculiarity of the particular needs for the pupil, its possibilities as for the apprenticeship within the discipline and more widely the skills of integration within the class, within the establishment and even outside it (Dubois, 2011). In this perspective, the teachers of physical education and sports have to demonstrate their knowledge and their understanding of another culture, to accept and to respect the diversity of this population and finally to make deliberate interventions suited for every pupil within the class. (Cagle, 2006; Columna, Foley & Lytle, 2010). This pedagogy of differentiation and integration of the children with specific educational needs requires a lot of preparation and a specific training to acquire experience in the teaching of physical education. 84 % of the teachers who recently qualified and 43 % of the trainees consider that their initial training did not prepare them enough to work with pupils with specific needs in ordinary physical education class (Vickerman & Coates, 2009). However, the integration of pupils with specific needs within an ordinary class is not an easy mission and presents diverse difficulties. In front of these problems, a great majority of the teachers oppose the inclusion of the pupils with specific needs in ordinary classes and this was demonstrated by various studies. (Avramidis, Bayliss & Burden, 2000; Scruggs & Mastropieri, 2000; Lavisse, 2009). The research question which emerged from this is: do Sport and Physical Education teachers have the necessary competences for an autonomous and optimal management of pupils with specific needs?

METHOD

Two hundred teachers randomly selected participated in our experiment. They all reside in the region of Sfax (Tunisia) working at primary, preparatory and secondary schools. (=35.5 years; Standard deviation=4.41). The argument for which this population was chosen is mainly of a professional order, because the physical education teachers are the main actors, directly concerned and involved in teaching on a daily basis. And more particularly here, in the teaching of pupils with specific needs.They answered the questionnaire anonymously (Dubois, 2011). Once questionnaires collected, data are collected and analyzed by means of the software Social Statistical Package for the Sciences, version 21.

RESULTS

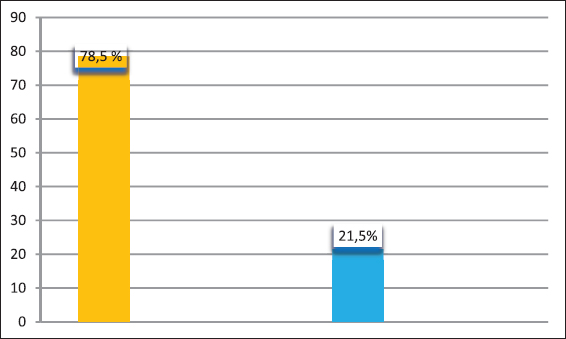

According to our results, the teachers of Sport and Physical Education do not consider themselves to be capable of taking care of the pupils with specific needs in ordinary physical education class presenting disorders or pathologies that are not frequently met due to a misunderstanding of what these disorders or pathologies are and the teaching approach to adopt for a better integration of these pupils. Informally it was reported by the trainee teachers, in charge of doing the questionnaires, that the physical education teachers did not wish to answer the questions about the disorders or the pathologies, the definitions of which they did not know. A great majority of establishments (67.5 %), and more particularly the projects of physical education in these establishments, did not plan a specific action (project, evaluation, activities etc.) to take up with pupils of particular needs, whereas 32.5 % of them did. Most of the teachers (78.5 %) consider that the handicapped pupils are more of a brake, than the opposite, while according to (21, 5 %) of them; they constitute rather a catalyst in the learning of each of the pupils. (Figure 1). Faced with these problems, 77, 5% of pupils with specific needs, who can be brought not to have a practice in the educational situation proposed by the teacher, are absent in the session of physical education.

Figure 1: The pupils with specific needs are rather a break than a catalyst for learning

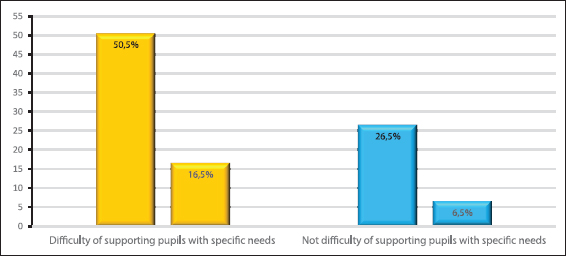

The bi – varied analysis of the fact of meeting pupils with specific needs and the difficulties to take care of their practice within their ordinary class are not dependent. (C²= 0.607, dl, 1 at p >.05). So, among the teachers of physical education, having met at least a pupil with specific needs during their teaching (67 % having answered yes), 50, 5 % of them had difficulties in taking care of these pupils. (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Crossing between encountering of pupils with specific needs in class of physical education and meeting difficulties to take care of these pupils

As regard, the effect of the qualification of the teachers on the nature of the support of the pupils with specific needs and more exactly the difficulties met during the intervention of the teachers on these pupils is rather negative (C²= 6,453, dl, 1 at p>.001 Significant difference). Indeed, 49.5 % of the physical education teachers among 68 % met difficulties to take care of the pupils with particular needs and 17.5 % of primary teachers of physical education among 32% answered that they cannot assume an effective care of the handicapped pupils. For that purpose, the request of the teachers for an in-service training relative to the pupils with specific needs is important for 57.5%. (Table 1).

Table 1: Crossing between the difficulties to take care of the pupils with specific needs and of the qualification of the teachers

DISCUSSION

According to the results analyzed previously, we noticed that the teachers of physical education encountered some difficulties to take care of the entirety and diversity of the student population which they teach. (Ludovic, 2000; Dubois, 2011).

Faced with these problems, a great majority of teachers oppose the inclusion of the pupils with particular needs in an ordinary classes and this was demonstrated by various studies. (Avramidis, Bayliss & Burden,2000;Kaufmann,1993;Scruggs & Mastropieri,1996; Peltier, 1997), and the obstacles confronted by the teachers of physical education are connected to the misunderstanding of the various disorders of pupils with specific needs because every child has a personal potential to which it will be imperative to adapt oneself (Cagle, 2006; Columna, Foley, Lytle, 2010). Certain forms of inability allow a simple change of the practice, in the wider context by a differentiated pedagogy. (Berzin, 2007; Dubois, 2011). Others require on the contrary a more complex form of reception and organization, to the extent of implementing an adapted specific course, when the establishment requires it and the means are made available. (Cachot & Poncet, 2013). Except for some disorders and pathologies such as the asthma and shyness. Indeed, the teachers of physical education usually meet these two types of pupils throughout their teaching, for that reason the teachers of physical education prefer to take care of the pupils with the most recognized particular needs allowing them to be able to direct, adapt their intervention to the specificities of these pupils without important adaptation of their insertion and their inclusion. This disparity in the care given to the pupils with specific needs can be explained by the absence of the official programs in physical education dedicated to this category of pupils with particular needs. In spite of the announcement of an article 38 in the chapter VII of official newspaper of the Tunisian republic in 2005 which insists on the right of the students with specific needs to receive the same knowledge as the normal ones and to benefit from a special education in accordance with their capacities in physical education. But unfortunately and according to the statistical data, we found that this category was marginalized and that the intervention of the teachers of physical education remains imperfect and unchanged to the pupils with particular needs. (Vickerman & Coates, 2009). In terms of conclusion, to allow teachers to take a real charge of these students, they have to be armed to lead such an intervention, to teach them in a autonomous and effective way.

CONCLUSION

The primary objective of this study was to describe and to assess the learning disabilities at the elementary and secondary levels taken care of by a multidisciplinary team by using the diagnosis tools and care available at present in Tunisia. It revealed the frequency of school difficulties spotted by the teachers and allowed to distinguish between the specific disorders of learning and the unspecified disorders of a secondary type in a neurological pathology or in precarious socio economic conditions. On the other hand, the profile and the severity of the disorders of the specific learners was not able to be studied because of the lack of standardized tests in Tunisia. This study also highlighted the lack of means of screening, diagnosis and care in Tunisia. Because of this Tunisian reality, the screening of these difficulties by the teachers and the harmonization of these difficulties with the pedagogy within schools should begin while waiting for the creation of units of consultation specializing in the diagnosis and the care of specific disorders of learning. To know the importance of the learning disorders in the field of handicaps would allow formulating these changes and these educational adaptations. The widest possible publication of the knowledge acquired on the learning disorders with every professional, medical, paramedical and teachers is a challenge. There are four ways to improve the schooling of the handicapped pupils. First, the strengthening of the cooperation between schools and medical, and social and health establishments and the implementation of the teaching units. Second, the increase of the number of reference teachers, who play an essential role in the quality of the schooling of the handicapped pupils, this allows to improve more the relation between the family and the teaching staff. Third, the continuation of the creation of educational units for integration, which constitute a privileged means of school inclusion at the secondary level, both in preparatory and secondary schools of general, technological or professional education, has to be accompanied by requirements as for the links with all the staff of the educational and health establishment. Finally, to incite the educational teams to exercise their creativity and their responsibility, to propose steps and new organizations, contributes to the success of all the pupils.